Willy de Roos

The roots of Ice Frontiers (Part II)

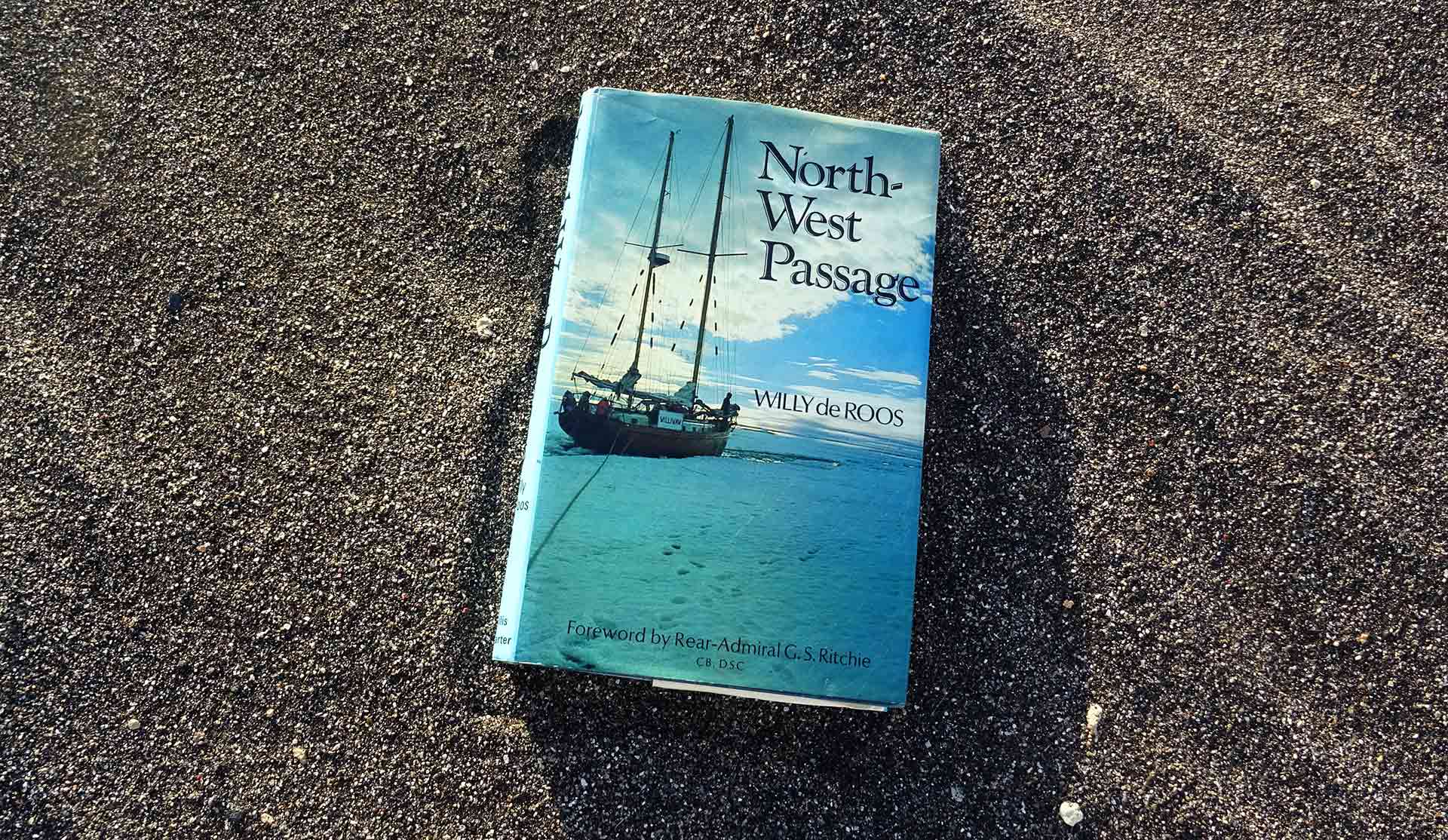

Willy de Roos can be recognized as one of the quiet founders of modern high-latitude sailing.

In 1977, he completed a solo transit of the Northwest Passage in a single season, without wintering over, escort vessels, or institutional support. He was not the first to sail the Passage, but he was the one who did so with the greatest economy of means—reducing technology, logistics, and spectacle to the essentials.

The Northwest Passage is the sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Canadian Arctic. For centuries, explorers hoped it would provide a shorter connection between Europe and Asia. Instead, it proved to be one of the most challenging maritime routes on Earth. Sailors went around South America centuries before they could reliably sail through North America.

The challenges of the Northwest Passage are structural, not incidental. It crosses an entire continent rather than skirting the tip of one. Depending on how its start and end are defined, the route exceeds 1,000 nautical miles. The Canadian Arctic is a labyrinth—an intricate archipelago of islands linked by narrow, often shallow channels that were, in the 1970s, poorly charted.

These channels trap sea ice well into summer. When the ice pack breaks up in spring, floes are driven by wind and current into narrow passages, forming choke points that can remain impassable for weeks or even an entire season. They can halt a vessel’s progress or trap it, exposing the hull to crushing forces. Because of this, navigating the Northwest Passage has often become a multi-year endeavor. Roald Amundsen himself took three years, wintering over as ice and geography dictated his pace.

What led Willy de Roos, in the 1970s, to imagine attempting this route alone is difficult to know. It was not an attempt to be first, nor to be fastest. It was an attempt to see how far one could go by reducing everything except commitment. He prepared meticulously and succeeded in a single season. At the time, the voyage was noticed mainly within specialized sailing circles, but it was treated more as a curiosity than as a turning point; its deeper significance only became clear years later.

With hindsight, his journey places him firmly in the lineage of sailors who transformed endurance into a way of life—alongside Joshua Slocum, Bernard Moitessier, and Francis Chichester. What unites them is not performance, but restraint.

Willy de Roos embodied the idea that the most meaningful frontiers are not geographical. They are internal. His voyages were less about pushing the edge of the map than pushing the edge of intention into action.

I met Willy de Roos a few years later, when he presented his film in Grenoble as part of the Connaissance du Monde lecture series. I must have been thirteen or fourteen. He left a lasting impression on me. I grew up reading the few books he wrote, over and over again.

It wasn’t his prose that drew me back. It was the man.

I was struck by his decision to leave a successful business and family life, well into his fifties, to pursue ambitious solo projects at sea. I admired his choice to sail single-handed, his meticulous preparation, his sober approach to risk, and his endurance.

Looking back more than forty years later, I am surprised that these aspects of his life resonated with me so early. Even more surprising is the clarity of a thought I remember having as a teenager: I hope that, one day, when I reach his age, I will be able to do something like that.

Today, as I navigate the uncertainty of assembling my own expeditions, I often find myself returning to a simple question:

What would Willy do?