Chasing Ice, 10 years later

The roots of Ice Frontiers (Part I)

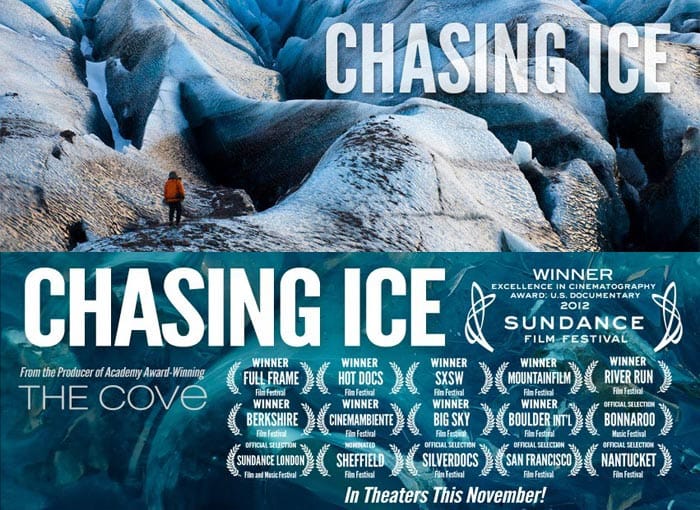

Chasing Ice is a 2012 documentary directed by Jeff Orlowski, following environmental photographer James Balog and the Extreme Ice Survey as they deploy time-lapse cameras across the Arctic and alpine regions to document glacier change. Premiering at the Sundance Film Festival, the film revealed—visually and unmistakably—the rapid retreat and collapse of ice on a planetary scale, transforming climate data into lived experience. Acclaimed for both its scientific contribution and emotional power, Chasing Ice received multiple honors, including an Emmy Award and a Peabody Award, and the Sundance Film Festival’s Excellence in Cinematography Award

When I first watched it, it was a transformational experience. For the first time, climate change was no longer abstract or statistical. Through time-lapse photography, glaciers began to move. They cracked, flowed, collapsed. They looked alive and they were dying.

It was, at its core, a scientific project. A massive data-collection effort, patiently documenting change that could not be seen otherwise. But it carried something more powerful than data: emotion.

The glaciers were no longer frozen backdrops; they became giant living forms, breaking apart, decomposing before our eyes. By accelerating time and the glacier disappearance, the movie triggered a sense of loss that charts and reports never could. The grief I felt after watching it revealed how attached I am to these landscapes.

Ice Frontiers grows out of that impulse: the need to document climate change not only with instruments, but with our emotions.

And yet, watching Chasing Ice again today, I feel a distance.

The message is heavy with doom, and perhaps it had to be. At the time, awareness was the battle. But we are past that stage now. The elements have already spoken. What we need today is not more proof of collapse, but ways to restore agency—ways to hold grief without surrendering to paralysis.

The film’s social dynamics also feel dated. The central character is not the climate, but the photographer. A lone hero, surrounded by others who serve his mission.

There is something uncomfortable about that framing now. Not because his determination wasn’t real—it was extraordinary—but because that generation also represents the world that created the problem. The future does not belong to the bearer of bad news. It belongs to younger generations who must live with what remains, who must make sense of an inheritance they did not choose, who need to imagine new forms of growth and development when existing models are failing them.

And there is one more tension that is harder to ignore today. Chasing Ice relies heavily on helicopters and fossil-fuel-intensive logistics. The images are breathtaking—but the contradiction is visible now. Calling attention to melting glaciers while burning enormous amounts of fuel to do so feels, ten years later, almost unbearable.

Ice Frontiers must learn from this. If we are to document the Arctic today, it must be done with an economy of means.

With restraint.

With slowness.

With humility.

The challenge is no longer to shock the world into awareness. It is to bear witness without reproducing the very systems that brought us here. To collect data that carries emotional weight without creating additional emotional burdens. To tell stories that leave room for grief—but also for resilience, ingenuity, and care.

The ice does not need another savior in shining armor. It needs witnesses who respect, nurture, and celebrate what’s left.