Bluewater Sailing: When Insurance and Taxes Set the Course

I expected the weather to set the course. I didn’t expect insurance and taxes to do it first.

When I first began considering a bluewater voyage, I expected winds, currents, and far-off landfalls to be the main challenges ahead. I imagined trade winds traced in sweeping arrows and ocean gyres acting like quiet conveyor belts. I embraced the romance of weather routing and celestial navigation.

Before I could get anywhere near a boat, however, I ran into obstacles that never appear on those charts: insurance clauses and tax codes.

When preparing a true bluewater passage—one that crosses oceans, borders, and years—financial considerations can shape the project as decisively as the wind. Sometimes more so. I can deal with weather uncertainty. I am willing to wait out a storm. I can live with imperfect forecasts. What I am not willing to accept is unlimited financial risk.

It quickly became clear that buying a boat to support this project meant learning to navigate a complex maze of insurance and tax constraints—many of which I did not even know existed a few months ago.

One Boat, Three Jurisdictions

To make sense of insurance and taxes, it helps to remember that every bluewater voyage sits at the intersection of three overlapping legal systems:

• The owner’s residence, which determines personal tax exposure, regulatory obligations, and vulnerability to litigation

• The boat’s registration, which functions as the boat’s legal home but may have little to do with where the owner lives

• The boat’s physical location, which governs customs, immigration, insurance validity, and local taxes

Unless a bluewater boat is registered where its owner lives and never sails outside that jurisdiction, it becomes the focal point where all three systems collide. The result is a whirlpool of overlapping and sometimes conflicting legal exposures—closer to whitewater rafting than sailing the tradewinds.

Insurance: Invisible Borders at Sea

At first glance, marine insurance resembles car insurance. There is liability coverage—protection against harm to others—and hull insurance, which covers damage to the boat itself. For coastal cruising, this model works reasonably well. Policies define neat geographic boxes: specific countries, coastlines, and maximum distances offshore.

Bluewater sailing does not fit neatly inside boxes.

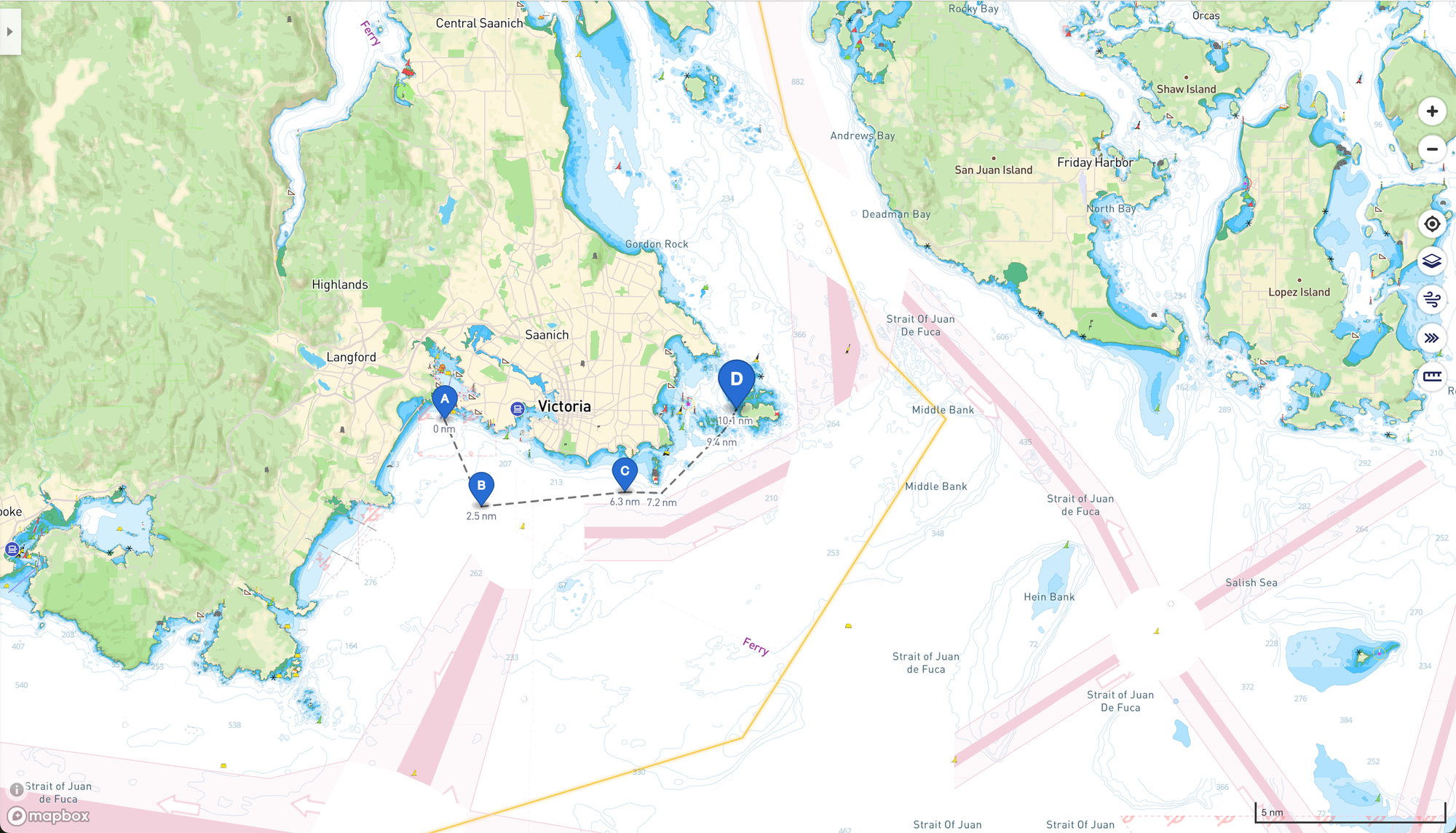

Jurisdictional boundaries are crossed organically, sometimes without much thought: sailing between U.S. states, from France to the Channel Islands, from California to Mexico, or from the San Juan Islands to British Columbia. Offshore passages amplify the problem by potentially involving a dozen jurisdictions, not all of which are planned landfalls. And the moment a sailing plan reflects the real capabilities of even a modest offshore boat, the pool of willing insurers shrinks dramatically.

Beyond geographic limits, policies are often riddled with nautical exclusions. Offshore distance limits—50 or 200 nautical miles from shore—can fundamentally alter routes or make certain passages impossible. Drawing these limits onto a chart is an instructive exercise: the “playground” one is insured to sail often looks far smaller than expected.

Weather-related exclusions add another layer of uncertainty. Some policies exclude damage incurred above a certain wind speed—sometimes as low as Force 6 Beaufort—raising uncomfortable questions about how such exposure would even be established after an incident. Others rely on named-storm exclusions. What was once limited to tropical cyclones now extends to an expanding catalog of named systems, often without clear geographic boundaries. In practice, sailing anywhere in the Atlantic between June and December may be enough to deny a claim—even if the boat was hundreds of miles from any storm.

Seasonal hurricane exclusions are another familiar constraint: leave hurricane areas or haul out. Simple in principle, difficult in practice. Getting a boat north in time, or safely onto the hard, is not always easy. In many cases, it feels wasteful, as large hurricane-prone regions can often be sailed safely during much of the season.

Finally, there are equipment-based exclusions: unfamiliarity with aluminum hulls, standing rigging age limits, fire extinguishers requiring annual testing. Individually reasonable, collectively daunting.

I have never had to file a marine insurance claim. I often wonder how these exclusions are handled in practice. Much likely depends on the underwriter—some have better reputations than others. Still, exclusions feel uncomfortably similar to pre-existing conditions in health insurance: a ready-made mechanism to deny coverage and shift the burden of proof onto someone who has just suffered a major loss.

The ocean says come. Most underwriters say don’t.

I am cautious not to go anywhere unless an insurer is willing to come along with me.

Taxes: The Hidden Reefs

If insurance defines where you may sail, taxes often determine how long you may stay.

Every arrival in a new jurisdiction carries a quiet risk: that the boat will be deemed imported. Duties, VAT, sales tax, use tax—each place has its own vocabulary for what can quickly become a devastating bill. Most countries tolerate foreign boats for a limited time, but always with conditions: no commercial activity, restricted cruising, firm departure deadlines, and often an absolute prohibition on selling the vessel locally.

The rules are not intuitive.

Here are a few scenarios I encountered while trying to understand the landscape.

A boat purchased in Florida by a Florida resident is subject to a 6% sales and use tax. A non-resident may keep a boat in Florida for a limited time without triggering use tax and can, under certain circumstances, extend that grace period.

Rhode Island is often cited as one of the most tax-friendly states for boats, with a sales and use tax rate of zero. That simplicity, however, comes with practical constraints: registration requires the boat to be physically present in the state, which complicates matters for buyers operating far from the East Coast.

In Europe, a boat registered in the EU and owned by a non-EU resident may circulate in EU waters for 18 months without triggering VAT. The same boat, owned by an EU resident, carries that tax burden everywhere in the world. The hull becomes fiscally anchored to the owner, not the water beneath it.

In New Zealand, boat prices generally include a 15% GST. Under certain conditions, that tax may not apply if the vessel is exported shortly after purchase.

These are only examples, and I am not even sure I fully grasped every subtlety. The point is that they are not edge cases. Every jurisdiction has its own quirks, and they are structural realities that quietly shape itineraries. Ignoring them can expose an owner to repeated, significant taxes at successive ports—or, just as unpredictably, to uneven enforcement that creates its own risks.

Learning to Navigate the Invisible

Sailors are trained to read weather systems, calculate tidal gates, and plan passages that work with the planet rather than against it. There is no equivalent training for navigating insurance policies and tax regimes. Yet a poor decision in this invisible domain can end a voyage just as surely as a dismasting.

Storms pass. Financial mistakes linger.

Bluewater sailing, it turns out, is not only about mastering the elements. It is about learning that some of the most consequential forces shaping a voyage never appear on the horizon at all.

They sit quietly in the paperwork—waiting to dictate the course.